Why Russians Are Lining Up for Soviet-Style Canteens

They haven’t lost their taste for Cold War-era comfort food.

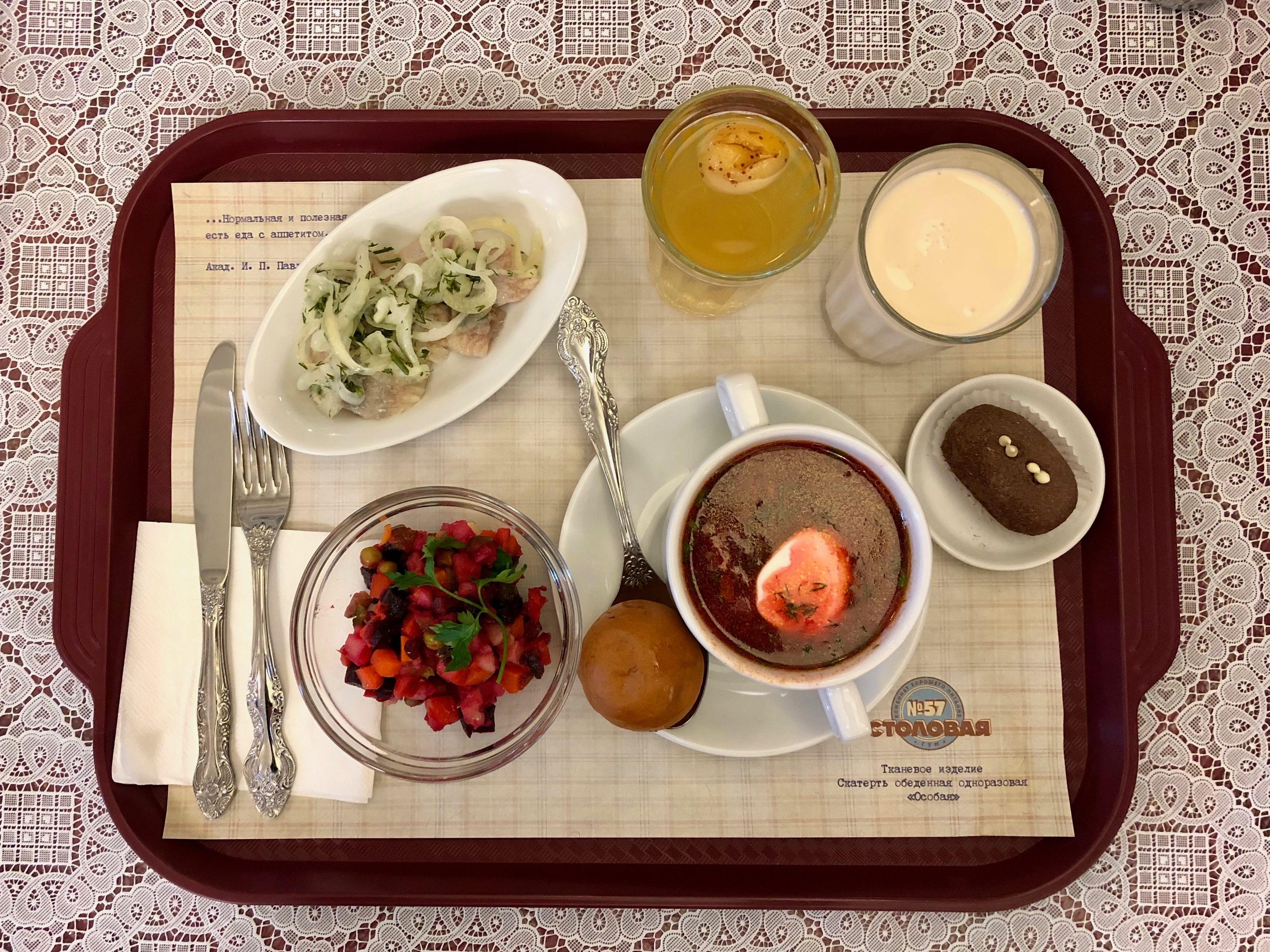

On a recent afternoon in Moscow, a line of hungry people stretched across the third floor of GUM, a stately 19th-century shopping arcade turned modern luxury mall overlooking Red Square. As the crowd waited to get into Stolovaya 57, a self-service cafe modeled on a Soviet workers’ canteen, a young woman snapped photos of the faux propaganda posters in the entryway. Inside, customers loaded their trays with fruity kissel, fuschia “fur coat” salad, and jellied pork. On the hot food line, a woman in a white uniform dished out mashed potatoes, Chicken Kiev, and stuffed cabbage and curtly called out, “Next order, please!” Murky jars of canned vegetables sat on shelves overhead. An abacus, like the kind used by Soviet shopkeepers, stood next to one of the cash registers. (Most diners paid by credit card.)

As I stood in line with Pavel Syutkin, a culinary historian who co-authored CCCP COOK BOOK: True Stories of Soviet Cuisine with his wife, Olga Syutkin, he told me the long wait was just another period touch. “When you go step by step, 20 minutes, half an hour, you really get an effect of being inside the Soviet past,” he said, recalling the anticipation that made the food taste better when he lived in Cold War-era Russia.

I asked Syutkin why, in 2019, a mostly Russian crowd would wait this long for a bowl of borscht served with a heavy dollop of Soviet kitsch. He explained that Stolovaya 57 is one of the cheapest places to eat near Red Square, and it was the Russian New Year holidays, a week when domestic tourists descend on Moscow. Still, there wasn’t much of a line outside the mall’s neighboring Cafe Festivalnoye, a food court-style spot serving baked potatoes and bliny, Russian crepes with sweet and savory fillings.

Aside from the prime location, Stolovaya 57’s popularity may have something to do with its name. Whether they’re from Moscow or a remote part of Siberia, Russians have a shared understanding of the word stolovaya, which means “dining hall” or “cafeteria.” Due to the Soviet legacy of public canteens, it’s shorthand for an affordable, filling, and predictable meal.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, food became a public matter instead of a private one. Preparing meals at home, the new Communist authorities argued, was an inefficient use of resources. State-run cafeterias were established to liberate women from “kitchen slavery,” improve nutrition, and exert control over the food supply.

According to Anya Von Bremzen, author of Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking, while a handful of these early canteens had genteel touches such as fresh flowers and live music, many were plagued by rats and served awful food. The cafeteria in the Kremlin was so bad that Lenin ordered multiple investigations. As it turned out, in addition to struggling with food shortages, the nascent Soviet state had replaced many professional chefs with ideologically pure but untrained ones. Still, nobody had promised the revolution would taste good. In the famine-stricken early 1920s, Von Bremzen writes, “food was fuel for survival and socialist labor.”

At Stolovaya 57, after Syutkin and I finally made it through the line and found a table, he explained that the quality of food and hygiene in the cafeterias improved in the 1930s. Regulators developed a set of standard recipes and policies as precise as how many grams of meat had to be in a serving of soup. These guidelines also formalized a culinary hierarchy in contrast to the vision of a classless society. Each recipe had three columns stating the requirements for different kinds of public dining facilities: more beef for bureaucrats, less for university students.

While the dishes in any Soviet cafeteria were supposed to be identical, in practice the quality varied widely. A large stolovaya in Moscow or Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) typically served far better food than the canteens in smaller towns.

Syutkin dined in one of these provincial cafeterias while working at a small-town newspaper in the Kaliningrad region, on the Baltic Sea coast. “It was really terrible,” he recalled, describing a particular meal of pork and squid cutlets as “the worst culinary memory in my life.” But the canteen also served the standard assortment of familiar dishes, and the solyanka, a hearty meat soup with pickles and lemon, wasn’t bad at all. (“It’s difficult to prepare solyanka [that’s not] tasty,” Syutkin added.) After he got a job in Moscow at TASS, the state news agency, he ate at a bigger cafeteria that offered five or six soups daily and a variety of salads, main dishes, and desserts at affordable prices.

Lackluster food wasn’t necessarily the fault of individual chefs, who had to make do with whatever ingredients the state provided. The Soviet food supply system routed the best stuff to high-level officials and larger state enterprises. “Access to good products was a symbol of your place in the social hierarchy,” Syutkin said. “Everybody could understand at what factory, at what ministry you work, [just by] looking inside your refrigerator.”

In 1959, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev signed a resolution to make the system of public food service “more massive, comfortable, and favorable.” Among other things, it called upon canteens to engage in “socialist competition” to improve conditions. A publication called The Female Worker documented cafeterias with great interest, lauding a particular dining hall in the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (now Belarus) for its ingenuity in using kitchen scraps to raise its own pigs. Workers’ commissions conducted inspections and pressed facilities to improve.

The need to account for how ingredients were used actually created some enduring favorites. At Stolovaya 57, I enjoyed kartoshka, a chocolate snack cake that became part of the Soviet canon in part because it handily used up leftovers.

While the relative bounty of the 1960s provided a reprieve after the lean years of World War II, in the 1970s and 80s, food shortages made life difficult for most Soviet citizens. “Those who could get a job at the canteen of a large enterprise were considered extremely lucky, since they often managed to take some food home,” notes Russia Beyond. That privilege didn’t come without risk, of course. Staff caught stealing could face harsh penalties, including imprisonment.

Despite the system’s flaws, Syutkin and most other Russians I spoke to have fairly positive, or at least neutral, feelings about Soviet cafeteria food. As Von Bremzen writes in Foreign Policy, “the truth about Soviet cuisine, of course, is that it was neither the rotten-potato hell of its bashers nor the cheery, comforting idyll of consumerist memory-mongers.”

Stolovaya 57, which opened in 2007, falls into the latter category. The brainchild of Bosco di Ciliegi, a Russian group with an Italian-inspired name that specializes in luxury shopping, it bills itself as an upgrade on the humble workers’ cafeteria. As the cafe’s website puts it: “They dreamt about good food, but cooked rather bad in Soviet canteens.”

It fits right in at GUM, which channels an idealized version of the Soviet Union alongside shops stocked with Agent Provocateur lingerie, Coach bags, and Bose speakers. On the first floor of the complex, a throwback grocery store called Gastronom №1 displays artfully assembled pyramids of sgushyonka, or sweetened condensed milk, in the iconic blue-and-white Soviet cans. It also carries sushi and Belgian beer.

“[Stolovaya 57] is a kind of a nostalgic note for those people who would like to remember the old-style canteen and good times and to have a really tasty meal,” GUM spokesperson Daria Ageeva said in an email.

It’s not the only modern eatery cashing in on Soviet nostalgia. Varenichnaya No. 1, a chain that serves varenyky (Ukrainian dumplings) and other classic comfort food, has 19 locations around Moscow. They’re wallpapered with pages from Pravda, which was once the official Communist Party paper, and staffed by waitresses wearing retro floral frocks with Peter Pan collars and ruffled white aprons. Down the street from one of the Varenichnayas, a cafe called Cheburechnaya USSR, which specializes in chebureky, a kind of meat pie, greets customers with a giant image of beaming, overall-clad Soviet workers.

According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, half of Russians 18-34 believe the breakup of the Soviet Union was a bad thing. Russians today also view Stalin more positively than Gorbachev. “A new generation of people in Russia have no knowledge of Communist Party meetings or long queues for basic foods,” the Syutkins write in their book. “They view the era as enigmatic and appealing.”

However, nostalgia isn’t the only thing motivating people to wait half an hour for plates of pickled herring. My 31-year-old friend Victor, who typically cooks at home and visits a mall food court for the occasional Vietnamese pho, points out that many of his peers are on tight budgets. Russia’s economy has been sluggish in recent years, and paychecks still don’t go as far as they used to.

According to a report by the Russian newspaper Rossiskaya Gazeta, the role of dining out in Russian culture is also changing. Restaurants used to be viewed as places where you dropped a lot of cash to celebrate a special evening, but increasingly they’re seen as spots to grab a quick bite.

“Why overpay?” Stolovaya 57’s deputy director Boris Soldatov told BFM.ru. “You can come to our canteen and have lunch or dinner with alcoholic beverages for 600 rubles [roughly $9].”

While you can no longer get a bowl of soup and a stack of meat and cabbage-filled piroshki for a mere ruble, cafeterias haven’t lost their appeal as a cheap, filling place to eat out.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook