Drink Like a Founding Father

Make one of President George Washington’s favorite cocktails.

This article is adapted from the October 19, 2024, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

As we enter what feels like the 800th year of this American election season, I can’t help but find myself thinking back to the guys who started it all. We’ve spent a lot of energy and legislative manpower attempting to decipher and interpret the language the Founding Fathers used—and how they intended it to apply to technologies and concepts that didn’t exist in their era.

And while there’s no denying that many of these men were ahead of their time in some ways, I question our tendency to put them on pedestals, be they literal marble ones or Tony Award–winning Broadway shows. Great thinkers they may have been, but they were also just people.

What’s more, they may have been a little drunk.

On September 14, 1787, just days before signing the Constitution, George Washington and his pals wracked up a bar tab at Philadelphia’s City Tavern worth the equivalent of $15,600 today. For 55 guests, the damage included 54 bottles of Madeira, 60 bottles of claret, 12 bottles of whiskey, seven large bowls of punch, eight bottles of cider, 22 bottles of porter, and 12 bottles of beer.

One can only speculate that this must have been a larger than usual celebration, especially since the bar bill includes a number of broken glasses. But the total still stands at two bottles of wine per person, plus beer, whiskey, and several glasses of punch—enough to knock most people today flat.

Brian Abrams, author of Party Like a President: True Tales of Inebriation, Lechery, and Mischief From the Oval Office, says it’s important to remember that consumption habits were generally different during the late 18th century. It was still common at the time to start the day with a small beer (usually around 3 percent ABV). “John Adams would drink a tanker of his cider every morning with his breakfast,” Abrams says.

Part of that was a coping mechanism for the physical and mental hardships of a rather difficult period in history. “As far as why all these old guys were drinking all the time, people’s bodies were riddled with all sorts of incurable diseases,” Abrams says. “Everyone’s walking around with whooping cough or typhoid, or they have splinters with tetanus in them, or bullets lodged in their bodies. These were not things that doctors could cure, so people just drank.”

Some of the Founding Fathers drank and ate more extravagantly than others. “[Jefferson] allocated more than $16,500 to wine during his first two terms, and $50 a day for food,” Abrams says. According to an economist Abrams consulted at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that works out to the equivalent of $300,000 to $350,000 for wine.

Although Jefferson’s Republican Party had a populist reputation in contrast to his Federalist counterparts, that didn’t stop him from drinking and dining like a French monarch. “[His cellar] was stocked with partridges, wild ducks, venison, squab, goose, pâté, rabbit, squirrel, crabs, and oysters,” Abrams says. Dinners were often eight courses, albeit with less stuffy table settings than was customary for the upper crust at the time.

“It was a friendly atmosphere,” Abrams says. “It was about ideas and discussions. It gave off a vibe where he didn’t seem stiff like those Federalists. But the truth is, they were all…I guess today we would call them all one-percenters.”

Appropriately, then, some of the Founding Fathers looked down upon the drinking habits of the lower classes. At the time, rum and whiskey distilling was on the rise.

In a letter in 1790, then treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton described spirits as “pernicious luxuries” and wrote, “The consumption of ardent spirits particularly, no doubt very much on account of their cheapness, is carried to an extreme, which is truly to be regretted, as well in regard to the health and the morals, as to the [economy] of the community.”

Both to make a dent in the fledgling nation’s lingering Revolutionary War debts and curb the drinking habits of its population, Hamilton suggested slapping a tax on domestically distilling spirits. It provoked immediate outrage in 1791 in western Pennsylvania, where many farmers straight-up refused to pay it.

By 1794, hundreds of “whiskey rebels” were starting violent protests, including burning down a house. The Whiskey Rebellion, as it became known, got so out of hand that George Washington himself had to take a militia of over 12,000 men down to Pennsylvania to quell it.

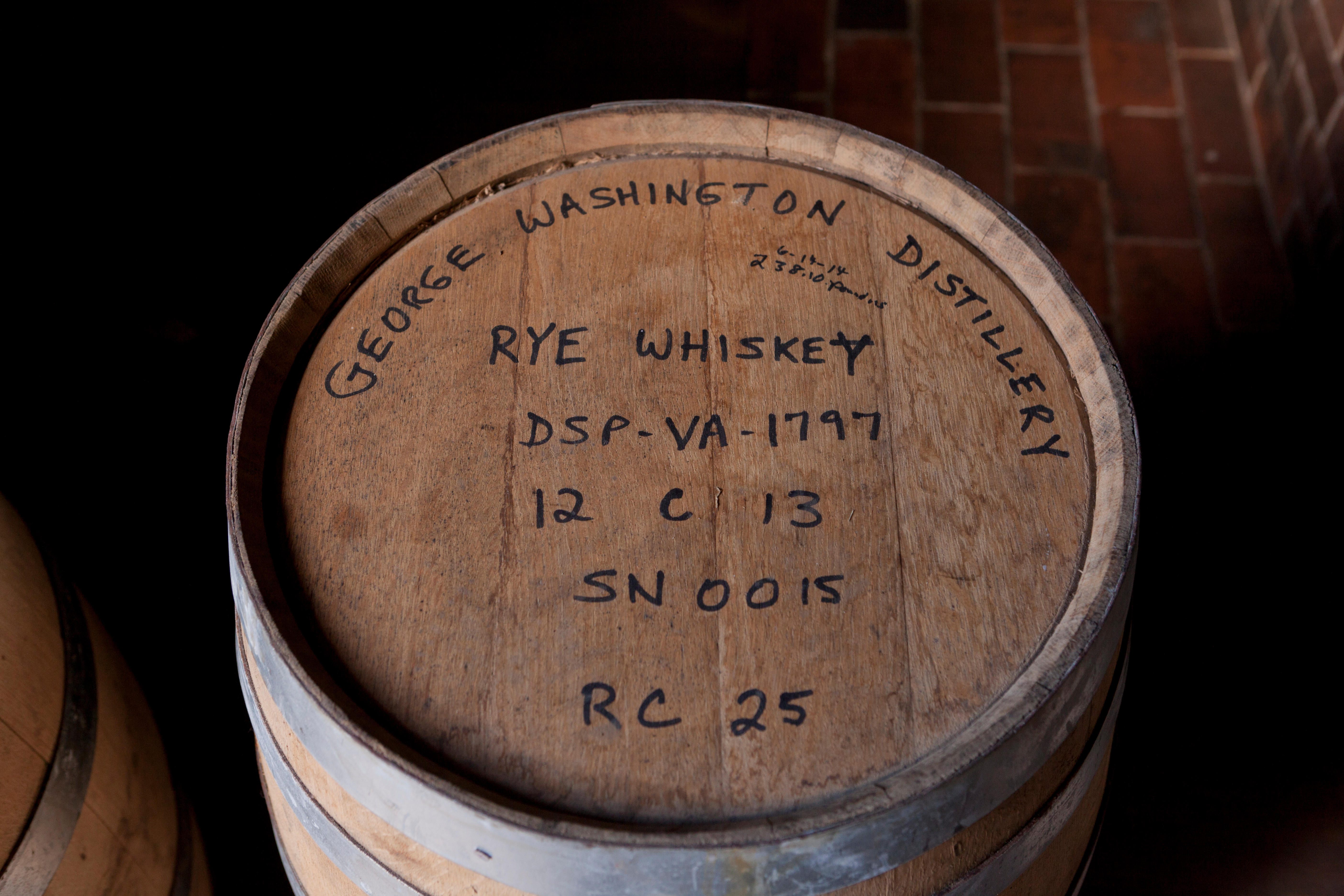

Just three years later though, Washington himself got into the whiskey business. In 1799, his distillery at Mount Vernon produced 11,000 gallons of whiskey. And while it’s unlikely he was the biggest boozer at his now infamous pre-Constitutional bender, we know he liked a tipple.

As Abrams writes in his book, “Washington and [French major-general François-Jean de] Chastellux bonded over booze,” helping to strengthen the alliance despite linguistic and cultural barriers. By the end of the Revolutionary War, Washington, who previously had mostly stuck to American beer and rum, had developed a taste for fine French wines.

Certainly, no one would advise drinking the quantities of liquor that were socially acceptable to consume in Washington’s time. But if you’re curious, you could always try a version of their poison of choice. According to Abrams, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association said Washington’s home-distilled firewater had a “pretty sharp taste”—not encouraging.

More promising is the cocktail that he carried while wandering in the woods. “He kept a canteen of this brandy-flavored beverage while he surveyed the Allegheny Mountains in September of 1784,” Abrams says. Sweet, tart, and very strong, it would have kept our nation’s first president both fortified and a little buzzed as he traipsed through the wilderness.

Given that the messy, conflict-riddled business of making this government in the first place drove the Continental Congress to drink, it feels appropriate to have a glass of something stiff on Election Day (just, you know, not so many that you trash a Philadelphia tavern).

If you’re feeling a bit anxious and exhausted by our democratic process, here are two easy things you can do right now: First, go register to vote if you haven’t already. Second, go make Martha Washington’s spiced, spiked sour cherry “bounce.” It needs to mellow for a full two weeks, meaning you’ll have a jar of liquid courage in your refrigerator when November 5 comes.

Martha’s Cherry Bounce

Ingredients

- 10 to 11 pounds fresh sour cherries, preferably Morello, or three jars (one pound, nine ounces) preserved Morello cherries

- 4 cups brandy

- 3 cups sugar

- 2 cinnamon sticks

- 2 whole cloves

- 1 piece fresh whole nutmeg

Instructions

-

Pit the cherries and put them in a large bowl.

-

Crush the fruit and strain the juice into a jar. Add the brandy and sugar, cover with a lid, and let sit for 24 hours. Shake the mixture occasionally.

- Put two cups of the juice over medium heat and add cinnamon sticks, cloves, and nutmeg. Let simmer for five minutes, then strain back into the jar. Set the liquid aside for another two weeks. Shake occasionally. If it’s still alive by then, serve at room temperature.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook